“Levelling up” the UK economy - Lessons from the evidence

For the past year the Industrial Strategy Council has had a specific workstream focused on the “places” foundation of the Industrial Strategy. That reflects the view that addressing regional disparities is a critical element of a successful Industrial Strategy, and the current level of public policy focus on this issue.

We carried out a review of the evidence on productivity differences across UK regions. The review sought to ascertain what we know about the nature and causes of UK regional productivity disparities – and what lessons the evidence may hold for UK regional policy. Regional productivity is measured as total income in an area (wages, rental income, and profits) divided by the total number of hours worked there. So it corresponds to the income generated by the “average” hour of work. The four main insights are:

1. UK regional productivity differences are very large.

- We looked across 41 UK regions representing small groups of counties, unitary authorities and council areas. In 2017 the most productive region was West Inner London, with productivity 2.1 times higher than Cornwall, the least productive region. This difference is large. The same comparison between the most and least productive regions would give numbers of 1.7 for Germany, 1.6 for France and 1.4 for Spain.

2. The UK has a long history of regional productivity disparities – but differences have not always been as large as they are today.

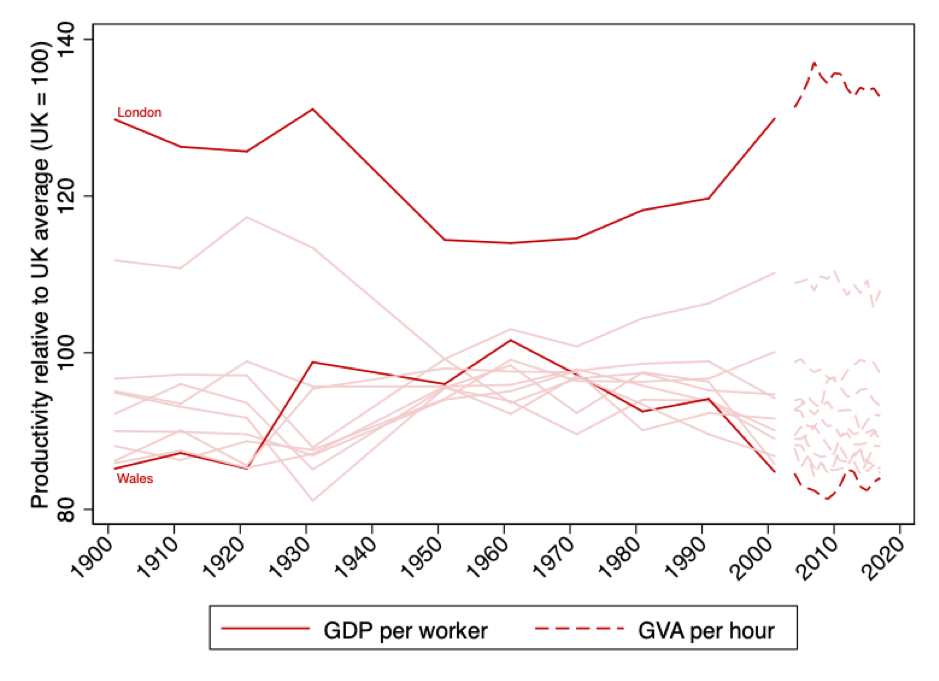

- Figure 1 shows the productivity of 9 broad UK regions relative to the UK average since 1900. It shows that in 1901, London was 30% more productive than the UK average, and Wales 16% less productive. These numbers are very similar today. However, as can be seen from the figure, the productivities of UK regions had converged significantly by the middle of the 20th century, only to diverge again in the decades since 1980.

3. Over the past decade, a few places have been “steaming ahead” in terms of their productivity. However, the set of places underperforming their potential is large and diverse.

- Over the past decade, cities such as London, Edinburgh, Bath and Bristol have been characterised by above-average productivity growth. However, not all cities have performed well. For example, cities such as Leicester, Nottingham and Sheffield have been falling behind in terms of their productivity. More generally, places in the South East of England and Scotland have boasted a better productivity performance than the rest of the country. Coastal regions, rural areas and the North of England have tended to do worse.

4. High-productivity regions tend to do better than low-productivity regions along a number of dimensions.

- High-productivity regions tend to have a better-skilled workforce, better local governance and management culture, attract more investment, and are more likely to be specialised in high-value economic activities. This makes it difficult to trace their success to any one local characteristic.

Figure 1: UK regional productivity differences between 1901 and 2017

Sources: Geary and Stark (2016), ONS (2019).

Our work also explored the potential explanations for these regional disparities. The answer is not that simple. There are three different narratives in the academic literature about the deep roots of spatial productivity differences. One emphasises differences in “fundamentals”: geography, local culture and infrastructure. Another emphasises “agglomeration”: the emergence in certain places of self-sustaining clusters of highly productive economic activities. The third emphasises “sorting”: the tendency for mobile workers to move to places with residents who are similar to themselves. In practice, their relative importance is hard to gauge, and all three are likely to account for some of the regional variation in productivity observed in the UK.

The Industrial Strategy aims to create “prosperous communities throughout the UK”. Our evidence review suggests that, in order to meet this goal, place-based policies should have three key features:

- They need to introduce a new degree of continuity into UK regional policy.

- The evidence shows that closing the gap between the UK’s least productive places and the rest of the country is a big task. Sustained productivity turnarounds do not happen overnight. Yet in recent decades, UK regional policy has been in a constant state of flux. There has been a tendency to abolish and re-create targets and institutions. Going forward, a more long-term approach would be beneficial.

- They need to be robust to different narratives.

- Given the difficulty of diagnosing the root causes of a region’s productivity performance, proposed policy interventions should be robust to different interpretations of the evidence. They also need to be realistic: dramatic improvements in a place’s productivity are rare, and meaningful change will require action across a range of policy areas.

- They need to keep a spotlight on places that are furthest from realising their productivity potential.

- Keeping the spotlight on regions underperforming their potential will not only contribute to balancing productivity growth across the UK, but also ensure that interventions are directed towards places where they have the best chance of making a difference.

The evidence suggests that it is possible to reduce regional disparities – but doing so will take time and will require significant, well-directed policy measures. The Industrial Strategy, together with the new Government’s “levelling-up” agenda, presents an opportunity to introduce greater continuity and ambition into UK regional policy.